About the article

DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.15219/em70.1306

The article is in the printed version on pages 55-60.

Download the article in PDF version

Download the article in PDF version

How to cite

E-mentor number 3 (70) / 2017

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Methodology and theoretical perspective

- Strategic design factors

- Political factors

- Concerns about competition with already existing online programs

- Cultural Lens

- Conclusions

- References

- Resisting the Global Campus: Strategic, Political and Cultural Dimensions Undermining Efforts to Build a Virtual Campus

About the author

Resisting the Global Campus: Strategic, Political and Cultural Dimensions Undermining Efforts to Build a Virtual Campus

Laurel Newman, Deborah Windes

Introduction

Using archival data and news reports, the authors analyze the initiation, implementation and decision to discontinue the University of Illinois's Global Campus for online learning. This case study focuses on the strategic, political and cultural dynamics involved in this attempt at educational innovation.

The organizational science literature is replete with exhortations about the importance of learning from organizational failures (Birkinshaw & Haas, 2016, pp. 88-93; Edmondson, 2011, pp. 48-55; Kayes & Yoon, 2016, pp. 71-79). The University of Illinois's attempt to launch the Global Campus provides an important opportunity to observe and learn from the failure of a major innovative educational initiative. The analysis of these events is enriched by examining the issues involved using three classic perspectives of organizational analysis; a strategic design perspective, a political perspective, and a cultural perspective (Ancona, Kochan, Scully, Van Maanen, & Westney, 2004).

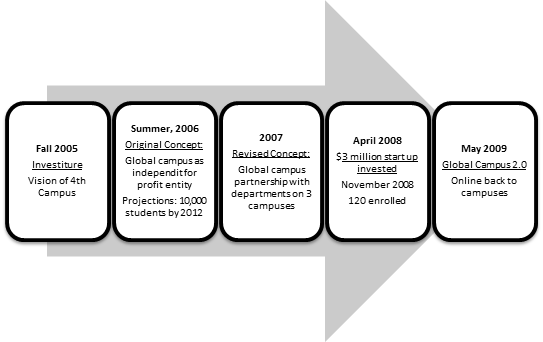

At his 2005 investiture, B. Joseph White, newly appointed President of the University of Illinois, described his vision of creating a virtual university as a fourth campus designed to provide online education (Heckel, 2005). This campus would be an addition to the three existing campuses in Champaign-Urbana, Chicago and Springfield, Illinois. By the summer of 2006, a proposal for the online "Global Campus" was being widely circulated. The explicit goal of the proposed Global Campus was to offer high quality programs with flexible, convenient access, in a way that was educationally innovative and financially sustainable (University of Illinois Global Campus Overview, 2007). The original concept outlined in the proposal was for the Global Campus to be established as an independently accredited for-profit entity that would offer online students access to University of Illinois programs in areas of high demand, such as nursing, business and education (Jaschik, 2007). The Global Campus would rely primarily on non-tenure track, part-time faculty teaching courses that would be delivered in an 8-week, accelerated format, designed to appeal to adult learners. The campus was expected to have sufficient enrollments to break even by 2010 and to reach an enrollment goal of 10,000 students by 2012.

The original proposal encountered a wall of faculty resistance. After intensive negotiations, the model was revised in a compromise designed to overcome faculty objections. The new campus would now be non-profit and would not seek independent accreditation. Courses and programs would be designed and supervised by faculty members in existing academic departments (Jaschik, 2007). The Board of Trustees approved the establishment of the revised initiative and the Global Campus opened their doors to new students in January 2008.

By April 2008, media reports indicated that after investing $3 million startup funds for IT, recruiting and service infrastructure, the Global Campus had only managed to enroll 10 students (Scholz, 2008). By November of 2008, enrollment had only reached 120 students and administrators were concerned about the lack of high demand baccalaureate completion partnerships from the other three campuses (Des Garennes, 2008).

After a failed attempt to win faculty approval of separate accreditation for the Global Campus, President White formed a task force to seek alternatives. The task force proposed a "reset" of the University's approach to online education entitled "Global Campus 2.0". In effect, the 2.0 proposal dismantled the Global Campus and returned responsibility for online education back to the three individual campuses of the University of Illinois.

The timeline in Figure 1 provides a summary of pertinent facts related to the history of the global campus.

Source: Timeline constructed from archival reports by Newman and Windes.

Methodology and theoretical perspective

Key events related to the initiation, implementation and elimination of the Global Campus were identified, using both news reports and archival documents. News sources included the local papers for each of the three campus locations, including the Chicago Tribune, the Champaign News-Gazette and the Springfield Journal Register. Senate minutes, resolutions and reports related to the Global Campus were identified via a search of the terms "global campus" or "GC" for each of the three campus senate websites, including the University of Illinois, Champaign/Urbana, University of Illinois, Chicago and University of Illinois, Springfield. A similar search was conducted for minutes and resolutions on the University Senate's Conference (the combined Senate for all three campuses) website, the website for the university's governing body, and the University of Illinois Board of Trustees.

The analysis that follows reviews the Global Campus initiative from three classic perspectives on organizational behavior: a strategic design perspective, a political perspective and a cultural perspective. Each of these perspectives emphasizes different elements of the initiative, the organization, and its environment, as contributors to the innovation's success or failure.

The strategic design perspective suggests that an innovation will be effective if the strategy and organizational design fit the conditions of its environment. Important factors in a strategic perspective include the competitive environment, the financing strategy, the marketing strategy, choices about production, and the organization's structure and design (Ancona et al., 2004; Nadler, Tushman, & Nadler, 1997).

The political perspective suggests that an innovation's effectiveness depends on successful negotiations with internal and external stakeholders who hold varying interests. Important considerations from a political perspective are to understand whom the relevant stakeholders are and what they have to gain or lose with the innovation (Ancona et al., 2004; Myeong-Gu, 2003, pp. 7-21).

The cultural perspective suggests that an innovation will be effective if it can be incorporated into the assumptions, norms, symbols and stories inherent in the existing organization. Understanding the underlying values and meanings attributed to innovation attempts is critical if an innovation is to be effective from a cultural perspective (Ancona et al., 2004; Büschgens, Bausch, & Balkin, 2013, pp. 763-81; Hogan & Coote, 2014, pp. 1609-1621).

Strategic design factors

Competitive Environment

The Global Campus initiative was launched in the summer of 2006. Online education was already a competitive field with nearly 3.5 million students, nearly 20% of all United States higher education students enrolled in at least one online course by the fall of 2006 (Allen & Seaman, 2007). The competitive environment was consistently identified in press coverage as a contributing factor to the failure of the global campus initiative, as illustrated by the following quote:

...there were a number of contributing factors, not least of which was increasing competition for online students, which pitted Global Campus against dozens of low-cost, Web-based operations as it sought to grow enrollment and recoup its initial investment. "We were entering a market that was simply becoming more competitive all the time," said Terry Bodenhorn, a history professor at the Springfield campus who was then serving as the chair of the system-wide University Senate's Conference. (Kolwich, 2009)

Financial Strategy

Rather than pursuing an incremental build up, the Global Campus initiative invested in administrative infrastructure upfront. An initial investment of $3.9 million in fiscal year 2008 grew to nearly $10 million worth of expenses, which exceeded revenues by fiscal year 2009 (Approve Fiscal Year 2008 Internal Financing Program for Global Campus, 2008). The large upfront investment put pressure on tuition prices, which ranged from $495 to $900 per credit hour (Approve Tuition Rates, Global Campus Programs in Recreation, Business and Global Safety, Fiscal Years 2008 and 2009; Approve Global Campus Tuition Rates for University of Illinois Graduates, 2008). The need for enrollments drove decisions about programming, a choice that was later criticized in the Global 2.0 report:

The current Global Campus has pursued matters of scale by setting numerical target enrollments and profit goals and then selecting and designing programs that can be "scaled" to meet those goals...Global Campus 2.0 would certainly seek scalability. But rather than doing so by setting targets and then designing programs accordingly, Global Campus 2.0 would work in the opposite way, starting with quality, sustainable programs that have a track record of success, and then allocating resources to help them grow in appropriate ways and at appropriate rates to meet social needs and market demand. (Burbules et al., 2009)

Production strategy

Another controversial strategic choice included in the Global Campus initiative was to separate course design from course delivery, a model widely adopted by for-profit online universities as a method for keeping costs low. Faculty criticism of this model is reflected in the following quote from a campus senate report:

...the dominant model of course development expressed in the Global Campus proposal: regular faculty develop high quality content, and lower-cost adjunct instructors do most of the delivery (at a rate apparently envisioned to be in the range of $3K-$4K per section). While other, more collaborative models are not ruled out, the basic organizational framework and business strategy of the proposal seem to assume this division of labor: and, indeed, if lowering production costs to achieve "up-scalability" is the primary value, some such division seems inescapable. Unfortunately, this is not the recipe for quality. It does not reflect best practice in some of the leading online programs on this campus. And it makes no provision for ongoing, continuous improvement in teaching, which requires the close collaboration of course content providers, designers, and instructors. Moreover, knowledge changes, technologies change, approaches to online teaching are continually changing - and these issues of content, form and pedagogy are highly interdependent. Quality education - particularly at the envisioned levels of undergraduate degree completion and graduate degree programs - is not a routine matter in which course "content" once developed, can simply be replicated for courses year after year (to be "delivered" by remote-controlled adjuncts hired on an enrollment-driven basis to do so). Ongoing development, updating, and redesign will require the continuous involvement of faculty experts in the subject areas. (Aminmansour et al., 2006)

Organizational Structure and Design

One of the most controversial strategic choices was the decision to establish the Global Campus as a separate, fourth campus organized as a limited liability corporation (LLC). The online programs offered by the Global campus would compete directly with existing online programs offered at the other three University of Illinois campuses. Thus, while directing additional resources to expand online offerings was a welcome decision, the organizational design choice to do this by creating a separate LLC entity was not:

We are proud of the successful online education programs (including UI on-line) at the three campuses; and we support the appropriate expansion of such programs as a component of a comprehensive University experience. Created and taught mainly by the full- time faculty, these online degree programs are indistinguishable from their on-the-ground traditional counterparts. We question the wisdom and efficiency of establishing a separate structure that will undoubtedly compete with existing programs. (Aminmansour et al., 2006)

Facing widespread resistance on this point from all three campus senates, this strategic choice was quickly reversed prior to implementation. The Global Campus was now to be called the Global Campus Partnership and to work more closely with the existing academic structure:

Thomas P. Hardy, a spokesman for the Illinois system, confirmed that the online program would now be nonprofit, and that academic programs would remain connected to existing departments. Hardy said that administrators had wanted the structure they proposed originally because they wanted it to be "a little more nimble and to respond to the market more quickly than perhaps you would get through the traditional academic unit structure". (Jaschik, 2007)

Low cost strategy

The choice to focus on keeping costs down, rather than creating innovative approaches, also garnered criticism:

Innovation is just as important as quality and the Global Campus needs to be about innovation in online teaching and learning, not only reduced costs and increased access (indeed, innovation will be essential to achieving both of the latter). The proposal assumes a "Blackboard" style of course design and delivery that is already becoming anachronistic for many online programs. We believe this to be a mistake, and a serious weakness of the proposal. (Aminmansour et al., 2006)

Political factors

University of Illinois, like most public universities in the United States (AAUP Joint Statement on Governance of Colleges and Universities, n.d.), has a long history of commitment to shared governance. The University of Illinois Statutes state, "As the responsible body in the teaching, research and scholarly activities of the University, the faculty has inherent interests and rights in academic policy and governance" (University of Illinois Statutes, 2017).

As stakeholders, faculty of the University of Illinois viewed the Global Campus initiative as counter to their interests in a number of ways:

Lack of faculty input

Faculty expressed concerns that they were not involved in the original conception of the Global Campus initiative. This was perceived as a threat to faculty rights with respect to shared governance, particularly in curricular matters:

We believe that the proposed model has been developed with far too little input from those on our campus (and presumably also on the other two existing campuses) with the most experience in online teaching, and in positions of responsibility for the very sorts of programs under consideration - from the faculty who teach the courses through the department and college executive officers to the key campus administrators. The Global Campus initiative will fail if they do not feel that they share ownership of it, and that it is something with which they not only are willing to be associated but want to be associated; and yet few of them have even been consulted about it in any meaningful way to date. It therefore is not surprising that it is seriously flawed in many respects. (Aminmansour, 2006)

Lack of faculty oversight going forward

The perceived threat to shared governance rights was not restricted to the origination of the Global Campus initiative, but built into the ongoing operation of the proposed model.

The proposal needs to make clearer provisions for ongoing significant university faculty involvement in, and control over, initial and continuing course development, not as a discretionary option but as a basic feature of Global Campus courses. (Aminmansour et al., 2006)

Concerns over quality and reputation

The Global Campus, as a freestanding entity, was also seen as a threat to the quality and reputation of the University of Illinois. A threat to the university's reputation implies a potential loss of status for the faculty employed by the university system.

If the Global Campus initiative is to receive significant faculty support, the development and articulation of a sound academic model that promotes and sustains the educational quality traditionally associated with the University of Illinois will be essential. (Bodenhorn, 2006)

(...) the University of Illinois "brand" (in the current manner of speaking) is generated by the quality and reputation of the other three campuses; and however successful the Global Campus may be as a teaching enterprise, there will always be an interdependence of status - both perceived and real - that gives all three existing campuses a stake in how the Global Campus represents this University. For many people around the state, around the country, and around the world, the Global Campus may well become a prominent part of the public face of the University of Illinois - for better or for worse. We must attempt to ensure that it is for the better. (Aminmansour et al., 2006)

Concerns about competition with already existing online programs

Prior to the announcement of the Global Campus initiative, all three campuses had been increasing their online offerings. This was particularly true at the Springfield campus, which at the time offered 20 academic programs online, with 25% of their total headcount being comprised of exclusively online students (University of Illinois Springfield Senate Global Campus Task Force Report, 2006). Concerns about the possible diversion of resources from these efforts arose (University of Illinois Chicago Senate Town Hall Meeting on the Global Campus Initiative, 2006), as well as concerns about whether the Global Campus programs would compete with these less well-funded efforts:

We already know that the demands of the Global Campus will require our faculty and staff to choose between competing priorities, work for the Global Campus or work for our campus. In Phase Two, when partnerships end, we see direct competition between the GC and campus based programs. With online students accounting for around 25% of our total, UIS has much to lose. We ask whether it is wise to help build an entity that has the capacity to put our online programs in jeopardy, either by losing current levels of enrollment or future growth. If the Global Campus came to us, not as our potential competitor in the form of a for-profit LLC insisting on the use of part-time faculty and a centralized curriculum, but as an organization committed first and foremost to helping us expand and improve our offerings according to our local customs and values, we would be more than willing to find ways to partner. (University of Illinois Springfield Senate Global Campus Task Force Report, 2006)

Cultural Lens

Cultural conflict with profit driven motive and emphasis on the bottom line

In addition to creating concerns from a structural perspective, the proposal to create a separate, for-profit LLC violated the values and norms held by faculty members in the existing institution:

The Global Campus Initiative Final Report describes a for-profit Limited Liability Company (LLC). While this business model may appear to provide certain advantages, many of our faculty are concerned by such a departure from our "traditional academic culture". The "for-profit" nature of the LLC raises many concerns. While we recognize that the Global Campus should be financially sustainable, would the motivation to create profits lead to an over emphasis of the "bottom-line" and, ultimately, begin to effect the academic decision making of the Global Campus? Would it not be better for the LLC to be a "not-for-profit"? (Kaufman, 2006)

Threat to identity as a selective institution

A separate, less selective admission process for the Global Campus gave rise to concerns about the institution's identity going forward:

We have real concerns about the reconcilability of a program model that admits everyone who meets a (presumably fairly low) minimum standard with the profile of a university with high standards of admission and correspondingly high expectations for student performance and degree completion. (Aminmansour et al., 2006)

Concerns about changes to the meaning of a University of Illinois degree

In the original proposal, there was no stated intention to differentiate the diplomas of graduates from Global Campus programs. This led to concerns about the true meaning of a University of Illinois degree, given differing admission and program completion standards:

We are concerned that, with no differentiation between a degree from the "Global Campus" and the traditional degree from our three existing campuses, the value of the traditional UI degrees at our (other) three campuses may be diluted and diminished by association, and by the indistinguishability of academic credentials. (Bodenhorn, 2006)

Separation of traditionally bundled faculty roles

The Global Campus model limited tenured and tenure-track faculty roles to "subject matter experts" who had input into course design but not into course delivery. This plan violated notions about the role of faculty in the education process:

The proposal contemplates courses that would be created and developed by UI faculty, but taught by non-faculty. Decoupling course development from teaching is deeply problematic. Teaching is an iterative process, a complex multidimensional activity that involves interaction between the faculty, the students, and the materials over time. It should be a continuous and unbroken loop. Separating course development from teaching is a hallmark of training, rather than education. (Bodenhorn, 2006)

Threat to tenure system

The choice to hire part time and full time faculty who were not part of the tenure review process also violated closely held values and norms:

The USC is deeply concerned about the fundamental absence of a real faculty - meaning fulltime, tenure-track faculty with the protection of academic freedom - in the proposed Global Campus, especially in the formative and mature phases. The intended involvement of regular UI faculty in the initial planning and supervision of courses and degree programs notwithstanding, we see a campus staffed mainly by non-faculty staff who are given the responsibilities of delivering courses to students. We have serious concerns about the educational responsibility and probable resulting quality of this approach. (Bodenhorn, 2006)

Conclusions

In response to the failure of the Global Campus to generate projected enrollments and revenues, it was ultimately dismantled. A new taskforce, convened by President White, proposed Global Campus 2.0, a new plan that redistributed online offerings to each of the three campuses. The only centralized function that remained was UI Online, an office charged with coordinating web page listings and responding to inquiries about the online programs offered by the three campuses. UI online also facilitated collaboration for system-wide issues that benefited from a coordinated response, such as state authorization and accessibility compliance.

Under the Global Campus 2.0 reconfiguration, the three campuses experienced incremental growth in their online programming and enrollments. Between 2009 and 2017, the number of degree programs offered increased by about 50% to a total of 15 bachelor and 46 master degrees. The number of certificate programs also grew by about 25% to a total of 78 certificate programs (University of Illinois Online Catalog, 2017 DATE). In addition, the Urbana campus had significant involvement with Coursera as a platform to offer MOOC courses, certificates and degree programs. A recent review of Coursera's website indicates over 70 active courses provided by the University of Illinois (Coursera Course Catalog, 2017).

The authors' review of the events surrounding the initiation, implementation and dismantling of the Global Campus suggests that it is important to understand innovation attempts from a multidimensional perspective. For innovations to be effective, the organization's strategy and design must fit the conditions of the environment, the interests of both internal and external stakeholders must be negotiated, and cultural factors need to be considered to ensure that the innovation will fit within the organization.

In the case of the Global Campus, the initiative did not deliver as envisioned due to difficulties that encompassed these strategic, political and cultural challenges. Unfortunately, it is often the case that the strategic aspects of initiatives are decided on without a thorough understanding of the political and cultural consequences. Even if the strategy proposed for the Global Campus had been perfectly developed and executed, the political and cultural challenges would have still posed significant threats to the success of the initiative. In the wrap up of the report, where the President's taskforce recommended the dismantling of the original plan and a distributed online approach, the following quote emphasizes the costs of not using a multidimensional approach:

As David J. Gray, Senior Vice President at the University of Massachusetts, and former CEO of UMassOnline said at a recent UPCEA conference in Boston, "Vast resources, elegance of models and the best technology all pale in importance relative to institutional buy in." Gaining that buy-in, from faculty, from campus units, and from administration at all levels across the campuses, is what this proposal is designed to accomplish. (Burbules et al., 2009)

References

- AAUP Joint Statement on Governance of Colleges and Universities. (n.d.) Retrieved from https://www.aaup.org/report/statement-government-colleges-and-universities.

- Allen, A., & Seaman, J. (2007). Online nation: Five years of growth in online learning. Sloan Consortium Survey Report.

- Aminmansour, A., Anderson, T.H., Burbules, N., Hirschi, M.C., Lesht, F.L., Marshall, K.A., Mortensen, P.L. et al. (2006). UIUC senate Global Campus task force report.

- Ancona, D.G., Kochan, T.A., Scully, M., Van Maanen, J., & Westney, D.E. (2004). Managing for the future: Organizational behavior & processes (3rd ed.). South Western College Pub.

- Approve Fiscal Year 2008 Internal Financing Program for Global Campus. (2008). Board of Trustees. University of Illinois.

- Approve Tuition Rates, Global Campus Programs in Recreation, Business and Global Safety, Fiscal Years 2008 and 2009 and Approve Global Campus Tuition Rates for University of Illinois Graduates. (2008). University of Illinois.

- Birkinshaw, J., & Haas, M. (2016). Increase your return on failure. Harvard Business Review, 94(5), 88-93.

- Bodenhorn, T. (2006, September 6). Senate's Conference Letter on Global Campus.

- Burbules, N., Hulse, C., Kaufman, L., Schroeder, R. Wassenberg, P., Watkins, R., & Wheeler, R.A. (2009). Redesigned Global Campus: Final report.

- Büschgens, T., Bausch, A., & Balkin, D.B. (2013). Organizational culture and innovation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(4), 763-81.

- Coursera Course Catalog. Retrieved from www.coursera.org/illinois.

- Des Garennes, C. (2008, November 4). UI president: Global Campus needs accreditation. The News-Gazette.

- Edmondson, A.C. (2011). Strategies for learning from failure. Harvard Business Review, 89(4), 48-55.

- Heckel, J.B. (2005, September 23). Joseph White presses campus to aim high. News-Gazette.

- Hogan, S., & Coote, L. V. (2014). Organizational culture, innovation, and performance: A test of Schein's Model. Journal of Business Research, 67(8), 1609-1621. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.09.007

- Jaschik, S. (2007, January 12). Death for for-profit-model. Inside Higher Ed.

- Kaufman, E. (2006, December 1). UIC senate response to President White's request for advice on global campus.

- Kayes, D.C., & Yoon, J. (2016). The breakdown and rebuilding of learning during organizational crisis, disaster, and railure. Organizational Dynamics, 45(2), 71-79.

- Kolwich, S. (2009, December 3). What doomed global campus. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/09/03/globalcampus.

- Myeong-Gu, S. (2003). Overcoming emotional barriers, political obstacles, and control imperatives in the action-science approach to individual and organizational learning. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 2(1), 7-21.

- Nadler, D., Tushman, M., & Nadler, M.B. (1997). Competing by design: The power of organizational architecture. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Scholz, R. (2008, April 6). UI's Global Campus starting small. News-Gazette.

- Unversity of Illinois Chicago Senate Town Hall Meeting on the Global Campus Initiative. (2006, October 10).

- University of Illinois Global Campus Overview. (2007). Office-of-the-President. University of Illinois.

- University of Illinois Online Catalog. www.online.uillinois.edu.

- University of Illinois Springfield Senate Global Campus Task Force Report. (2006, December 12).

- University of Illinois Statutes Article II Section 3B. Retrieved from http://www.bot.uillinois.edu/governance/statutes.

Resisting the Global Campus: Strategic, Political and Cultural Dimensions Undermining Efforts to Build a Virtual Campus

This study examines the initiation, implementation, and ultimate elimination of the Global Campus Initiative at the University of Illinois. Using archival data and media reports, the authors examine the events surrounding the initiative through three classic organizational behavior lenses: a strategic design perspective, a political perspective, and a cultural perspective. These perspectives posit that the effectiveness of an organizational innovation depends on whether the strategy and organizational design fit the conditions of its environment; whether internal and external stakeholders believe it is in their interests to adopt the innovation; and whether the innovation can be incorporated into the cultural norms and values of the organization. The data indicates that there was insufficient attention paid to all three areas, which led to the ultimate disbanding of the effort. The outcome of the Global Campus Initiative suggests that organizations seeking to innovate should first address the strategic, political, and cultural forces that may pose a challenge to successful implementation.